Meghalaya | The Tussle over Para 12A of Sixth Schedule by Fabian Lyngdoh

SHILLONG | May 19, 2019:

The legal maxim, "ignorance of law excuses no one" (ignorantia legis neminem excusat) is a principle holding that a person would not escape liability for violating that law merely because he/she is unaware of its existence. The doctrine assumes that a law has been promulgated, and citizens are supposed to know, when it is published through recognized procedures. This implies that not only the lawyers, but every citizen in a State is assumed and expected to know or be aware of the existence of the law. Registered lawyers are persons authorized by law to take up the profession of advocating people in litigations in the court of law as an economic activity, a trade or a business. But the law requires that all should know the law, and none is excused for not knowing it. With this note, I present in this article my analysis of the disputed Para 12A of the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution of India for initiating further debate and discussion among the lawyers as well as among the general public alike.

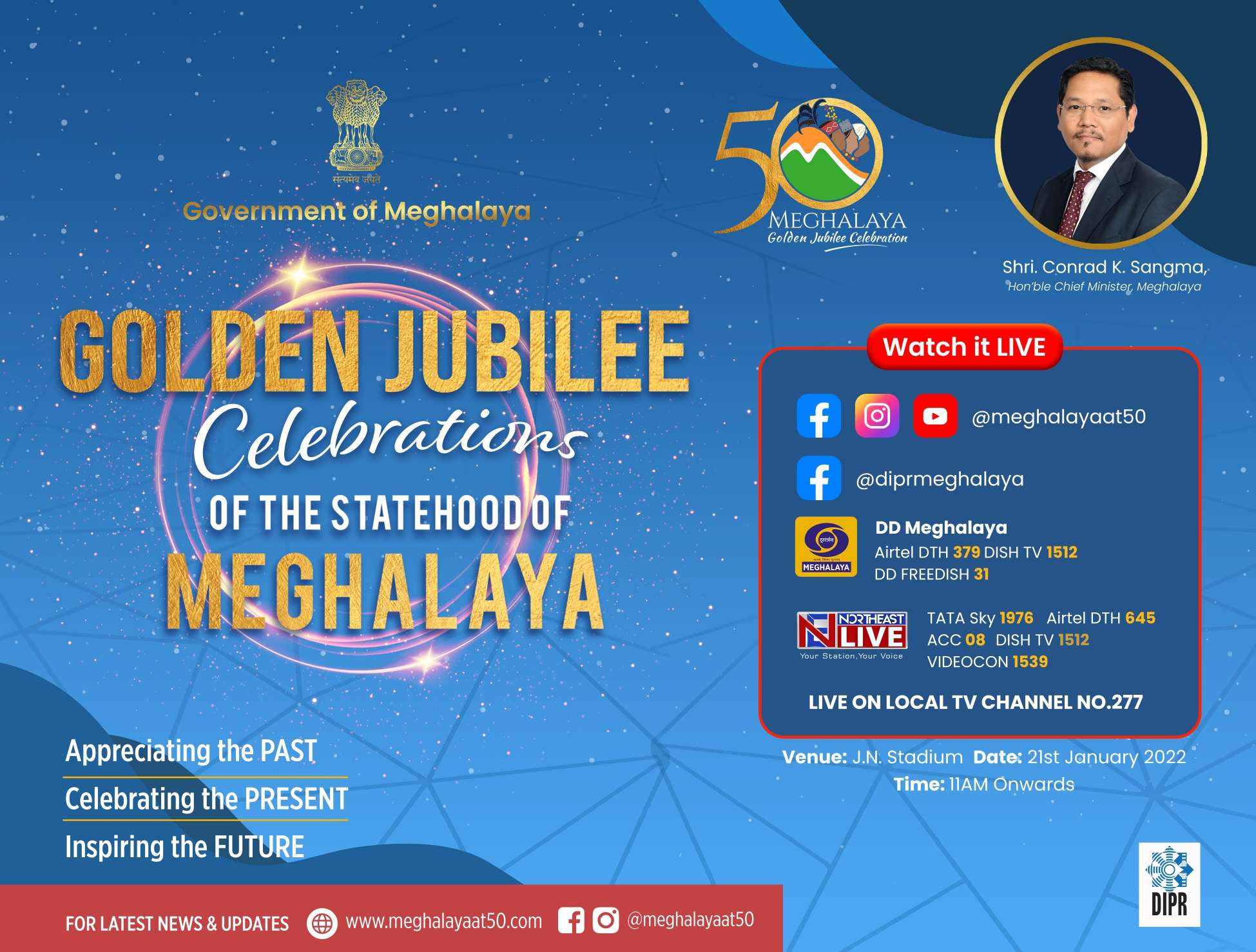

The Para 12A of the Sixth Schedule takes its present form by the North Eastern Areas (Reorganization) Act, 1971 when Meghalaya became a full-fledged State. It is an outgrowth of Para 12, which as originally enacted, states that no Act of the Legislature of the State in respect of matters specified in Para 3 of the Sixth Schedule, on which the District Council or Regional Council may make laws, shall apply to any autonomous district or autonomous region unless the concerned district council or regional council, by public notification directs that such State legislation would be applicable to the autonomous district or autonomous region over which it has jurisdiction, subject to such exception or modification as it thinks fit. Hence, according to Para 12 of the Sixth Schedule, it is the prerogative of the District Council or Regional Council to decide whether the State laws with regards to matters specified in Para 3 of the Schedule shall be applicable or not within its territorial jurisdiction. Today, the original paragraph 12 is applicable only in the State of Assam.

Para 12A states that if any provision of alaw made by the District Council in the State of Meghalaya with respect to anymatter specified in sub-paragraph (1) ofparagraph 3 of the Sixth Schedule, or if any provision of any regulation madeby the District Council under paragraph 8 or paragraph 10 of the Schedule, isrepugnant to any provision of a law made by the Legislature of the State ofMeghalaya with respect to that matter, then, the law or regulation made by theDistrict Council, whether made before or after the law made by the Legislatureof the State of Meghalaya, shall, to the extent of repugnancy, be void and thelaw made by the Legislature of the State of Meghalaya shall prevail.

Analysis of the provisions of Para 12A shows that it does not speak of, "a Bill or a provision of a Bill passed by the District Council," to be screened and rejected by the State Government, but it speaks of, "a provision of a law made by the District Council." The provision relates to a law, which means a Bill that has been passed by the District Council, and assented by the Governor. A Bill that has been passed by the District Council but has not been assented by the Governor is not a law, but only a Bill which Para 12A is not concerned about. Moreover, Para 12A does not speak of the repugnancy of a provision of a law made by the District Council to the learned opinion of the District Council Affairs (DCA) Department or the State Law Department, but it speaks of the repugnancy of a provision of a law made by the District Council, to a provision of a law made by the State Legislature. Hence, a provision of a law made by the District Council shall be void only to the extent of its repugnancy to a provision of the State's law.

Who has the constitutional mandate tojudge the repugnancy of a provision of a law made by the District Council to aprovision of a law made by the Legislature? Certainly it is a domain of theJudiciary (Meghalaya High Court) to judge the extent of repugnancy inparticular litigations where the law of the District Council and the Law of theState legislature happen to be in contest. If I establish my claim over certainrights on the basis of a provision of a law made by the District Council, andanother person stakes his claim over the same right in the Judiciary on thebasis of a provision of a law made by the State Legislature, then the provisionof the State law would prevail and the judges would decide the matter in favourof the other person in the instant case. But if no one is disputing my claimover those rights on the basis of a provision of a District Council's law, thenthat provision of a District Council's law is not repugnant to anything at all. That is the meaning of the phrase, "tothe extent of repugnancy, be void." The concept, "the law made by theLegislature of the State shall prevail", does not imply that the law made bythe District Council stands annulled or repealed lock stock and barrel.

Para12A does not authorize the DCA Department of the State Government with a veto power to reject wholesale the Bills passed by the District Council on mere supposed or perceived repugnancy. The matter in question is the repugnancy of a provision of a law to be decided in the Judiciary, and not the repugnancy of a Bill to be decided by the DCA Department of State Government. But what is happening in reality is that and the DCA Department on the advice of the State Law Department had rejected or kept pending many Bills duly passed by the District Council without giving the chance of testing repugnancy in the court of law.

The DCA Department is assuming the role ofa guardian of Khasi customs and tradition, which is the constitutional mandateof the District Council. In 2013, the DCA Department rejected the "Khasi HillsDistrict (Nomination and Election of the Syiem, Deputy Syiem and Headmen ofLangrin Syiemship) (Third Amendment) Bill, 2013" on the supposed ground that theprincipal Act of the Langrin Syiemship, was intended to serve and protect theindigenous Khasis in Langrin Syiemship, and it was opined that the proposedamendment by the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council (KHADC) to delete thephrase "both of whose parents are Khasi by birth who", from Section 2(d) of theprincipal Act would have a disastrous effect to the indigenous Khasis of theSyiemship.

Who has the constitutional mandate to interpret and safeguard Khasi customs and traditions, the State Government or the District Council? This episode seems to suggest that the State Government is all out for the preservation of the customs and traditions of the indigenous people, while the District Council seems to lack that concern. But it may also indicate that the State Government is usurping the authority of interpreting and protecting the Khasi social customs which is the domain of the District Council according to paragraph 3 of the Sixth Schedule.

The spirit of Para 12A of the SixthSchedule is not to circumscribe the legislative power of the District Council,but it is only to safeguard against infringement of fundamental human rights ofthe citizens, on grounds of the Sixth Schedule. Due to the play of party politicsand personal interests, some laws had indeed been passed in the KHADC not forpublic interest, but just to serve the personal interest of someone in thepower circle. On the other hand, forsome other vested interests, Para 12A seems to have also been utilized by thosein the State Government to reduce the status of an autonomous district councilto that of a department of the State Government, and thereby, affected theautonomy of the District Council as the guardian of customs and traditions aswell as the cultural identity of the indigenous community.

Citizens should come forward formeaningful intervention in this political tussle. The people are in need ofsocio-economic development and civic welfare, as well as safeguard of humanrights in a democratic social order. The proper domain of the State Government is with the maintenance ofthe social order in the legal context; and in socio-economic development andcivic welfare of the citizens. On the other hand,indigenous people also feel the need for preserving territorial and culturalidentity. The properdomain of the District Council is with conservation of tradition, and guidance tothe evolution of customs, and the maintenance of social order in the culturalcontext. The State Government should have nothing to do with the nominationand election of the Syiem of Hima Langrin, and the District Council should have nothing to dowith the construction of multi-story buildings, metalled roads, or themanagement of urban waste and sanitation which are not elements of Khasicustoms and traditions.